United States - DHL 15.00 € + 7.70 € /kg

United States - DHL 15.00 € + 7.70 € /kg

- Save

16.00 €

Octomore 10.2

70 cl, 56.9%In stock143.20 €159.20 €

Lagavulin 12 Year Old (2019 Special Release)

70 cl, 56.5%In stock128.80 €![]()

Talisker 10 Year Old

70 cl, 45.8%In stock37.60 €![]()

Arran Sherry Cask - The Bodega

70 cl, 55.8%In stock52.80 €![]()

Edradour 12 Year Old 2011 Cask Strength (Batch 1)

70 cl, 57.8%In stock103.20 €- Save

15.20 €![]()

Peat's Beast Batch Strength - Pedro Ximénez Sherry Wood Finish

70 cl, 54.1%In stock40.00 €55.20 € - Save

16.00 €![]()

Octomore 13.1

70 cl, 59.2%In stock127.20 €143.20 € - Save

16.00 €![]()

Octomore 13.2

70 cl, 58.3%In stock143.20 €159.20 € ![]()

Lagavulin 12 Year Old (2020 Special Release)

70 cl, 56.4%In stock128.80 €![]()

Glenfarclas 2004 Autumn Edition 2021

70 cl, 53.5%In stock92.00 €![]()

Ballechin 17 Year Old 2005 Small Batch Burgundy (Cask #327 - 334)

70 cl, 53.5%In stock159.20 €![]()

Octomore 14.2

70 cl, 57.7%In stock159.20 €![]()

Octomore 12.2

70 cl, 57.3%In stock159.20 €![]()

Ballechin 19 Year Old 2004 Small Batch Manzanila (Cask #269 & #274 & #275)

70 cl, 55%In stock180.00 €![]()

Octomore 14.3

70 cl, 61.4%In stock207.20 €![]()

Talisker Dark Storm (1 Liter)

100 cl, 45.8%In stock63.20 €![]()

Bunnahabhain 10 Year Old 2012 (Cask #900604) - Signatory Cask Strength

70 cl, 64.9%In stock114.40 €![]()

Scapa Glansa

70 cl, 40%In stock47.20 €![]()

Talisker x Parley Wilder Seas

70 cl, 48.6%In stock65.60 €- Save

8.00 €![]()

Glenfarclas Heritage 60° Cask Strength

70 cl, 60%In stock71.20 €79.20 € ![]()

Glenfarclas 15 Year Old

70 cl, 46%In stock71.20 €![]()

Arran 17 Year Old Limited Edition

70 cl, 46%In stock131.20 €![]()

Port Charlotte MC: 01 2009

70 cl, 56.3%In stock111.20 €![]()

Caol Ila 16 Year Old 2007 (Cask #5) - Signatory Cask Strength

70 cl, 58.5%In stock137.60 €- Save

12.00 €![]()

Ballechin 15 Year Old Small Batch Cask Strength - 2nd Release

70 cl, 58.9%In stock99.20 €111.20 € ![]()

Deanston 10 Year Old Bordeaux Red Wine Cask

70 cl, 46.3%In stock48.80 €![]()

Isle of Jura The Paps 19 Year Old

70 cl, 45.6%In stock87.20 €![]()

Arran Quarter Cask - The Bothy

70 cl, 56.2%In stock43.20 €![]()

Octomore 15.2

70 cl, 57.9%In stock159.20 €![]()

Ledaig Rioja Cask Finish - Sinclair Series

70 cl, 46.3%In stock39.20 €![]()

Bunnahabhain 12 Year Old

70 cl, 46.3%In stock48.00 €![]()

Ballechin 12 Year Old 2009 Sherry (Cask #344) - Straight From The Cask

50 cl, 58%In stock75.20 €![]()

Glendronach Cask Strength Batch 12

70 cl, 58.2%In stock85.60 €- Save

10.40 €![]()

Talisker 8 Year Old (2021 Special Release)

70 cl, 59.7%In stock92.80 €103.20 € ![]()

Arran 11 Year Old Small Back Australian Red Wine Cask

70 cl, 55.7%In stock73.60 €![]()

Craigellachie 13 Year Old Miniature

5 cl, 46%In stock6.40 €![]()

Glen Garioch 12 Year Old

70 cl, 48%In stock39.20 €![]()

Talisker Port Ruighe

70 cl, 45.8%In stock48.00 €- Save

11.20 €![]()

Caol Ila 11 Year Old 2010 (Cask #107) - Signatory Cask Strength

70 cl, 57.1%In stock100.00 €111.20 € ![]()

Ledaig 10 Year Old Miniature

5 cl, 46.3%In stock4.80 €- Save

24.00 €![]()

Allt-á-Bhainne 20 Year Old 2000 (Cask #3) - Signatory Cask Strength

70 cl, 52.4%In stock199.20 €223.20 € ![]()

Benrinnes 15 Year Old - Flora & Fauna

70 cl, 43%In stock63.20 €![]()

Benriach 22 Year Old Triple Distilled

70 cl, 46.8%In stock159.20 €![]()

Ardbeg Smoketrails Manzanilla Edition (1 Liter)

100 cl, 46%In stock110.40 €![]()

Glenlivet 16 Year Old 2006 (Cask #900815) - Signatory Cask Strength

70 cl, 60.7%In stock122.40 €![]()

Octomore 15.1

70 cl, 59.6%In stock148.80 €![]()

Lagavulin Distiller's Edition

70 cl, 43%In stock97.60 €- Save

16.00 €![]()

Balvenie 15 Year Old Madeira Cask

70 cl, 43%In stock143.20 €159.20 € ![]()

Lagavulin 16 Year Old

70 cl, 43%In stock87.20 €![]()

Aberlour 12 Year Old Non Chill-filtered

70 cl, 48%In stock44.00 €![]()

Laphroaig PX Cask Triple Matured (1 Liter)

100 cl, 48%In stock79.20 €![]()

Glendronach 12 Year Old Miniature

5 cl, 43%In stock4.80 €![]()

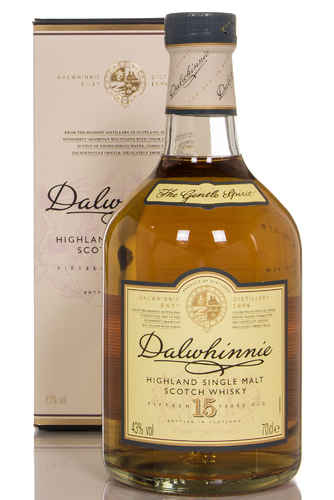

Dalwhinnie 15 Year Old

70 cl, 43%In stock44.80 €![]()

The Glenlivet Distiller's Reserve Triple Cask Matured (1 Liter)

100 cl, 40%In stock63.20 €![]()

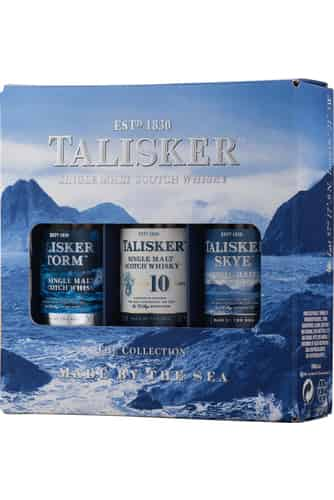

Talisker Miniature Set - 3 x 5 cl

15 cl, 45.8%In stock15.20 €![]()

Glen Garioch The Renaissance 3rd Chapter 17 Year Old

70 cl, 50.8%In stock103.20 €![]()

Lagavulin 12 Year Old (2022 Special Release)

70 cl, 57.3%In stock139.20 €![]()

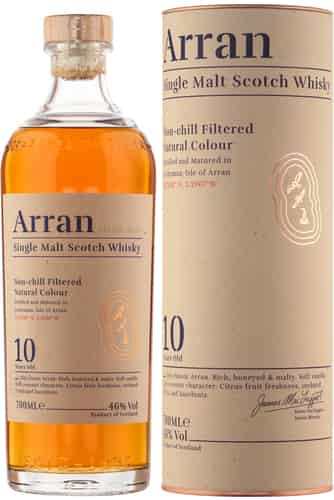

Arran 10 Year Old

70 cl, 46%In stock39.20 €- Save

9.60 €![]()

Kilchoman Small Batch - Bourbon & Oloroso & Cognac

70 cl, 50.6%In stock81.60 €91.20 € ![]()

Loch Lomond Miniature Set - 3 x 5 cl

15 cl, 46%In stock16.00 €

Sorry, we didn't find anything. Please try changing your search criteria.

Scotch Single Malt Whisky History

Single malt Scotch whisky is rightly recognised as the most complex spirit on the planet. With as broad a range of styles and niches as could be imagined, there is a malt for all tastes and preferences. At first sip, flavours flow over the palate in a beguiling glissando. Single malt is a testament to human ingenuity and skill, and strength in simplicity.

Whilst blended whiskies continue to be bestsellers, it is single malts that have become synonymous with luxury, class and deft power. To be classed as a single malt whisky, it must only have been strictly with just malted barley, and from only one distillery. Of course, it must also meet the necessary criteria for all Scotch whisky, it must be: made in Scotland, matured for at least three years, and in nothing other than oak barrels. No additions are allowed, other than water and some caramel colouring.

Each malt whisky starts its life with humble barley, which is malted through biological trickery, convincing it to germinate. This is sometimes done in the traditional style by hand. It is then dried, which can be a crucial moment for the flavour of the whisky, particularly in the case of peated malts. After this, it is ground and combined with water to make a sweet liquid known as "wort". Unfortunately named, perhaps, but this substance is integral to the final spirit. The wort is fermented in large tubs called washbacks, creating a strong beer.

This beer is then distilled a first time in the "wash still" to produce low wines- a relatively strong alcoholic substance at around 20-25%. The low wines are collected, and distilled a second time, and what is produced is known as "new make". A clear, almost vodka-like spirit, many whisky lovers would be shocked to learn that this liquid would later become the oft-thick, dark liquor they are familiar with.

This leads neatly on to the last part of single malt production, and possibly the most important for the whiskies overall flavour: maturation. Choice of cask can contribute a large part of a whisky’s taste, whether that be the vanilla and honey of ex-bourbon casks, the fresh berries of port casks or the Christmas cake of sherry casks. Of course, the other half of maturation is age- old whiskies, young whiskies, both have their merits, but only the most skilled distillers know the right time for each cask.

Single malt distilleries have been traditionally been grouped geographically into several regions: Campbeltown, Highland, Island (though not officially recognised by the SWA), Islay, Lowland and Speyside. Each have been said to have their own characteristics and history.

Campbeltown’s history is particularly fascinating. This peninsula jutting into the North Atlantic was once the populated with distilleries of all the regions, and could boast some 28 at the top of the 20th century. Sadly, a mere three remain, the others lost to economic hardship in the wake of prohibition and the Great Depression. The survivors are: Springbank, Glen Scotia and the relatively new Glengyle. Yet, what the region lacks in quantity it makes up for in quality, particularly Springbank, who make whisky of the very highest order, using their partial triple distillation techniques. The region has been known for imbuing the whisky with pungent smoke and briny qualities, though distilleries have made whiskies of all flavours and styles in this region.

The Highland region is by far the largest of all the regions, covering much of Scotland north of Glasgow. This is an extraordinarily large area, with a great range of styles contained. The more southern distilleries are known to produce lighter, floral drams, almost in keeping with the Lowland tradition. In the north, big, bold sweet whiskies. Whilst in the east, there are more sherried and fruity drams. In the west, one finds whisky influenced more by the North Atlantic air, and peat smoke. Of course, none of these are hard and fast rules, and a variety of great whisky is to be found right across the region.

Of all the regions, the Island grouping is perhaps the most controversial and certainly the most disparate. Here islands many hundreds of miles apart are grouped, from Orkney in the north, to Arran in the west. Yet there is a somewhat common flavour to these- a definite brine, and earthy funk is sometimes apparent. Controversy stems from its status as a region, widely acknowledged by whisky drinkers and salesman across the globe, but denied by Scotch’s governing body- the Scotch Whisky Association- who identify it with the Highland or Speyside regions.

Whilst the Highland region is the largest, perhaps the most famous and easily identified region is Islay. This small island is home to some of Scotch whiskies most iconic distilleries, the likes of Lagavulin, Laphroaig and Ardbeg are all found here. One of Scotland's oldest distilleries, Bowmore, has been on Islay for over 230 years. Despite this formidable history, innovation also flourishes here, with Bruichladdich’s creative rival and the new farm distillery Kilchoman both imposing in their own way. The region is known for a powerfully peated style of whisky, gained through drying the barley with the hot fumes of burnt peat, and a crisp salinity from the sea air that shrouds the island.

Like Campbeltown, the Lowland region is another that has suffered greatly in the past hundred years, with notable losses such as Rosebank and Ladyburn. The region is known for its lighter, floral malts, and its practice of triple distillation (which often means the whisky has a body similar to that of Irish whisky). The Lowland region lies between the border of England and Scotland, the start of the highlands, and is home to Auchentoshan, Glenkinchie and rejuvenated Bladnoch.

In the far north of the Highlands lies Speyside. Quite easily the most densely populated with distilleries, this region is home to more than half of the whisky-makers in Scotland. The region houses two of Scotland’s greatest whisky towns, Aberlour and Dufftown. Many of Scotch whiskies most notable distilleries are found here, such as the Balvenie, Glenlivet,Glen Grant and perhaps the most famous of all, Glenfiddich. The "Speyside Style" has undergone a marked evolution in the last few decades, having initially been much more similar to a north Highlander, with hints of salinity and peat. Now, the region is much more known for its sweetness and honey notes. However, Speyside also produces marvellous sherried whisky, nicknamed "sherry bombs", from the likes of Glenfarclas and Macallan. These whiskies excel with age too. It should also be noted that distilleries such as BenRiach have experimented to great success with heavily peated and interestingly finished whiskies.

As shown, single malt whisky dominates the Scottish nation, from the islands in the west, to the lowlands in the south there are distilleries to be found. Yet, it was not always the case that drinkers would be able to sample malts from many of these distilleries. It is only in the last 50 years or so that single malt bottlings have become common on our shelves. Prior to this, nearly all malt whisky produced in Scotland was sold to blenders to add flavour. In fact, some distillery managers in Islay considered the whisky to be "too intense" to be consumed by itself. It is Glenfiddich that we have to thank for "creating" the single malt market as we know it, their marketing campaign establishing it in the public mind.

Single Malt whisky is Scotland’s finest, most classy export after James Bond. Single malt whisky represents a bona fide gourmet spirit, made simply and delivered extraordinarily. More than just barley and water, the whisky seems to have distilled some of Scotland’s hospitality. It is a drink that brings people together, from Glasgow to Inverness, from glen to glen and island to island, the sound of glasses clinking is heard, alongside that old Gaelic toast: "Slainte!"